Tacotron2

NATURAL TTS SYNTHESIS BY CONDITIONINGWAVENET ON MEL SPECTROGRAM PREDICTIONS

ABSTRACT

- 본 논문은 텍스트에서 직접 음성 합성을 위한 신경망 아키텍처인 Tacotron 2에 대해 설명한다.

- 이 시스템은 문자 임베딩(character embeddings)을 mel-scale spectrograms에 매핑하는 recurrent sequence-to-sequence feature 예측 네트워크로 구성되며, 이어서 수정된 WaveNet 모델이 이러한 spectrograms에서 시간 영역 waveforms을 합성하는 vocoder 역할을 한다.

- 본 모델은 4.58 MOS를 얻은 전문적으로 녹음된 음성과 비교해서 4.53 MOS를 달성한다.

- design 선택을 입증하기 위해, 시스템의 주요 구성 요소(key components)에 대한 절제 연구(ablation studies)를 제시하고 linguistic, duration 및 F0 feature 대신 WaveNet의 input 조절로 mel spectrograms을 사용하는 것이 미치는 영향을 평가한다.

- 또한 본 논문은 compact acoustic intermediate representation를 사용하면 WaveNet 아키텍처의 크기를 줄일 수 있다는 것을 보여준다.

Index Terms— Tacotron 2, WaveNet, text-to-speech

1. INTRODUCTION

- 수십 년 동안의 조사에도 불구하고 텍스트에서 자연스러운 음성을 생성하는 것(text-to-speech synthesis, TTS)은 여전히 어려운 과제이다.[1]

- 시간이 지남에 따라, 다른 기술들이 그 분야를 지배해왔다.

- unit selection과 Concatenative synthesis, pre-recorded waveforms의 작은 단위를 서로 연결하는 과정[2, 3]은 수년 동안 최첨단이었다.

- Statistical parametric speech synthesis[4,5,6,7]은 Vocoder가 합성할 speech features의 부드러운 궤적을 직접 생성하며, boundary artifacts와 함꼐 연결 합성(concatenative synthesis)이 가졌던 많은 문제를 해결했다.

- 그러나 이러한 시스템에 의해 생성된 오디오는 종종 사람 말에 비해 흐릿하고 부자연스럽게 들린다.

- 시간 영역 waveform의 생성 모델인 WaveNet[8]은 실제 인간 음성과 어깨를 나란히 하기 시작하는 오디오 품질을 생산하며 일부 완전한 TTS 시스템에서 이미 사용되고 있다. [9, 10, 11]

- 그러나 WaveNet에 대한 입력(언어적 특징, predicted log fundamental frequency(F0) 및 phoneme durations)은 강력한 어휘(robust lexicon)뿐만 아니라 정교한 텍스트 분석 시스템을 포함하는 상당한 도메인 전문 지식을 필요로 한다.

- 문자 시퀀스에서 magnitude spectrogram을 생성하기 위한 sequence-to-sequence 아키텍처[13]인 Tacotron[12]은 이러한 언어 및 음향 feature의 생성을 데이터만으로 훈련된 단일 신경망으로 대체하여 전통적인 speech synthesis pipeline을 단순화한다.

- resulting magnitude spectrograms을 vocode하기 위해 Tacotron은 phase estimation에 Griffin-Lim algorithm [14]을 사용하고, 그 다음에 inverse short-time Fourier transform을 사용한다.

- Griffin-Lim은 WaveNet과 같은 접근 보다 characteristic artifacts 와 lower audio quality를 생성하기 때문에, 이것은 미래 신경망 vocoder 접근법을 위한 간단한 placeholder였다.

- 본 논문에서는 mel-spectrogram을 생성하는 sequence-to-sequence Tacotron-style model[12]과 수정된 WaveNet vocoder[10, 15]의 장점을 결합한 음성 합성에 대한 통일되고 완전히 신경망적 접근 방식을 설명한다.

- 정규화된 문자 시퀀스와 그에 상응하는 speech waveform에 대해 직접 학습된 본 모델은 실제 인간 음성과 구별하기 어려운 자연스러운 음성을 합성하는 방법을 배운다.

- Deep Voice 3[11]은 이것과 유사한 접근 방식을 설명한다.

- 그러나 Tacotron2와 달리, DeepVoice3의 자연스러움은 인간의 말과 견줄 만해 보이지는 않았다.

- Char2Wav[16]는 neural vocoder를 사용하는 end-to-end TTS에 대한 또 다른 유사한 접근 방식을 설명한다.

- 그러나 그것들은 different intermediate representations (traditional vocoder features)을 사용하고 모델 구조는 크게 다르다.

2. MODEL ARCHITECTURE

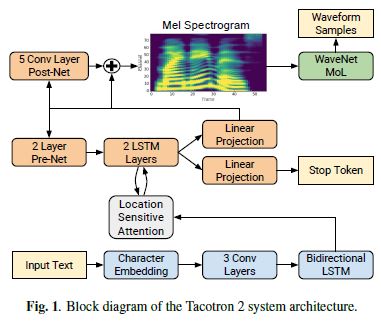

- 제안된 시스템은 Fig. 1.에 나타낸 두가지 구성 요소로 구성되어있다.

입력 문자 시퀀스(input character sequence)에서 mel spectrogram 프레임 시퀀스를 예측하는 recurrent sequence-to-sequence feature prediction network with attention

예측된 mel spectrogram frames에서 조건화된 time-domain waveform samples를 생성하는 WaveNet 수정버전

2.1 Intermediate Feature Representation

- 본 연구에서는 낮은 수준의 음향 표현(low-level acoustic representation): melfrequency spectrograms,을 선택하여 두 구성 요소를 연결한다.

- time-domain waveforms에서 쉽게 계산되는 표현을 사용하면 두 구성 요소를 별도로 학습할수있다.

- 또한 이 표현은 waveform samples보다 부드러우며 각 프레임 내에서 phase가 불변하기 때문에 오차 제곱 손실(squared error loss)을 사용하여 훈련하기 쉽다.

- mel-frequency spectrogram은 linear-frequency spectrogram(예를들면(i.e.) the short-time Fourier transform (STFT))과 관련이 있다.

- 그것은 인간 청각 시스템의 측정된 반응에서 영감을 받아 STFT의 주파수 축에 nonlinear transform을 적용하여 얻어지고 더 적은 차원으로 주파수 내용을 요약한다.

- 이런 auditory frequency scale를 사용하는것은 speech intelligibility에서 중요한 낮은 주파수에서 세부사항을 강조하는 효과가 있다. 반면에 높은 fidelity로 모델링할 필요가 없고 마찰음과 다른 시끄러운 파열음이 지배적인 높은 주파수 세부사항은 반강하는 효과가 있다.

- 이러한 특성 때문에, mel scale에서 파생된 특징들은 수십 년 동안 음성 인식을 위한 기초적인 표현으로 사용되어 왔다[17]

- linear spectrogram이 phase information를 버리는(손실되는) 반면, Griffin-Lim[14]과 같은 알고리즘은 이 버려진 정보를 추정할 수 있으며, 이는 inverse short-time Fourier transform을 통한 시간 영역 변환을 가능하게 한다.

- Mel spectrogram은 더 많은 정보를 삭제하여 어려운 inverse problem을 제시한다

- 그러나 WaveNet에서 사용되는 언어 및 음향 특징과 비교하면, mel spectrogram은 오디오 신호의 더 단순하고 낮은 수준의 음향 표현이다.

- 따라서 mel spectrogram에서 조건화된 유사한 WaveNet 모델이 근본적으로 neural vocoder로서 오디오를 생성하는 것은 간단해야 한다.

- 실제로, 본 논문은 수정된 WaveNet 아키텍처를 사용하여 mel spectrogram에서 고품질 오디오를 생성할 수 있다는 것을 보여줄 것이다.

2.2 Spectrogram Prediction Network

Tacotron에서와 같이 mel spectrograms은 50 ms frame size, 12.5 ms frame hop 및 Hann window function을 사용하여 단시간 푸리에 변환(STFT)을 통해 계산된다.

우리는 original WaveNet에서 조건화 입력의 주파수를 일치시키기 위해 5ms frame hop으로 실험했지만, 해당 temporal resolution(시간해상도?) 증가는 훨씬 더 많은 발음 문제가 발생하였다.

125Hz에서 7.6kHz에 걸쳐있는 80 channel mel filterbank를 사용하여 STFT magnitude를 mel scale로 변환하고 이어서 log dynamic range compression을 한다.

log compression전에, logarithmic domain에서 dynamic range를 제한하기 위해 filterbank output magnitudes가 최소 0.01로 잘린다.

이 네트워크는 attention과 encoder-decoder로 구성되어 있다.

Encoder

Encoder는 character sequence를 Decoder가 spectrogram을 예측하기 위해 사용하는 hidden feature representation로 변환한다.

입력 문자는 학습된 512차원 문자 임베딩을 사용하여 표현되며, 512차원의 문자 임베딩은 각 레이어 별 5 x 1 크기(즉,5개 문자)의 512개 필터를 포함하는 3개의 컨볼루션 레이어 스택을 통과하며, batch normalization[18] 와 ReLU 활성화가 뒤따른다.

Tacotron에서와 마찬가지로, 이러한 컨볼루션 레이어는 입력 문자 시퀀스에서 longer-term context(예:N-grams)를 모델링한다.

최종 컨볼루션 레이어의 출력은 512 units(256 in each direction)를 포함하는 single bi-directional[19] LSTM[20] 레이어로 전달되어 encoding된 features을 생성한다.

encoder output은 전체 인코딩 시퀀스를 각 decoder output step에 대한 fixed-length context vector로 요약하는 attention network에 의해 사용된다.

Attention

우리는 additive attention mechanism[22]을 확장하여 이전 decoder time steps의 누적된 attention weights를 additional feature로 사용하는 location-sensitive attention[21]을 사용한다.

이는 모델이 입력을 통해 일관되게(지속적으로) move forward 하도록 하여, 일부 시퀀스가 decoder에 의해 반복되거나 무시되는 잠재적 failure modes를 완화한다.

Attention probabilities은 inputs과 location features을 128-dimensional hidden representations에 투영한 이후 계산된다.

Location features은 31 length의 1-D convolution filters 32개를 사용하여 계산한다.

Decoder

Decoder는 한번에 한 프레임씩 encoded input sequence에서 mel spectrogram을 예측하는 autoregressive RNN이다.

이전 time step의 prediction은 먼저 256 hidden ReLU units의 fully connected layer 2개를 포함하는 small pre-net을 통과한다.

information bottleneck으로 작용하는 pre-net이 attention을 학습하는데 필수적인것을 발견했다.

pre-net output과 attention context vector는 1024 units로 구성된 2개의 uni-directional LSTM layers의 stack을 통해 연결되고 전달된다.

LSTM output과 attention context vector의 concatenation은 target spectrogram frame를 predict하기 위해 선형변환(linear transform)을 통해 투영된다.

마지막으로, predicted mel spectrogram은 전체적인 재구성을 개선하기 위해 예측에 추가할 residual를 예측하는 5-layer convolutional post-net을 통과한다.

각 post-net layer는 batch normalization과 5 x 1크기의 filters 512개로 구성되며 최종 레이어를 제외한 모든 filter에 tanh activations이 뒤 따른다.

또한 시간에 따른 constant variance 가정을 피하기 위해 Mixture Density Network[23,24]로 output distribution(출력분포)를 모델링하여 log-likelihood loss을 실험했지만, 이런 분포가 더 훈련하기 어려웠고 더 나은 소리 샘플로 이어지지 않았다.

spectrogram frame prediction과 동시에, decoder LSTM output과 attention context의 concatenation은 scalar에 투영되고 sigmoid activation을 통해 전달되어 output sequence가 완료될 확률을 predict한다.

이 “stop token” prediction은 모델이 항상 고정된 기간 동안 생성하지 않고 생성을 종료할 시기를 동적으로 결정할 수 있도록, 추론 중에 사용된다.

특히 생성은 이 확률이 임계값 0.5를 초과하는 첫 번째 프레임에서 완료된다.

Network의 convolutional layers는 0.5 확률의 dropout[25]을 사용하여 정규화되고 LSTM layers는 0.1 확률의 zoneout [26]을 사용하여 정규화된다.

추론 시간에 output variation을 도입하기 위해, 0.5 확률의 dropout은 the autoregressive decoder의 pre-net 레이어에만 적용된다.

“reduction factor”를 사용하지 않는다. 즉 각 decoder 단계는 single spectrogram frame에 해당한다.

2.3. WaveNet Vocoder

mel spectrogram feature representation을 time domain waveform samples로 반전시키기 위해 WaveNet architecture의 수정된 버전을 사용한다.

original architecture와 같이 30개의 dilated(확장된) convolution layers가 있으며, 3개의 dilation cycles로 분류된다. 즉, layer k (k = 0 … 29)의 dilation rate은 \(2^k(mod 10)\)이다.

spectrogram frames의 12.5 ms frame hop으로 작업하기 위해, 3개의 layers 대신 2개의 upsampling layers만 conditioning stack에 사용된다.

softmax layer로 discretized buckets을 예측하는 대신, PixelCNN++ [27]과 Parallel WaveNet [28]을 따르고 10-component mixture of logistic distributions(MoL)을 사용하여 24kHz에서 16-bit 샘플을 생성한다.

logistic mixture distribution를 계산하기 위해 WaveNet stack output은 ReLU activation를 통과한 이후 linear projection을 통해 각 mixture component의 parameters (mean, log scale, mixture weight)를 예측한다.

loss는 ground truth sample의 negative log-likelihood로 계산된다.

3. EXPERIMENTS & RESULTS

3.1. Training Setup

training process는 먼저 feature prediction network를 자체적으로 학습한 다음, 수정된 WaveNet을 첫번째 network에서 생성된 outputs에 독립적으로 학습한다.

feature prediction network를 학습하기 위해, 단일 GPU에 batch size 64인 standard maximum-likelihood training procedure(decoder side에 predicted output 대신, correct output을 제공(teacher-forcing으로 불리기도 함))를 적용하였다.

\(B_1 = 0.9, B_2 = 0.999, \epsilon = 10^-6\) 그리고 50,000번 iterations 이후 learning rate를 \(10^-3\)에서 \(10^-5\)로 기하급수적으로 감소시키는 learning rate의 Adam optimizer를 사용한다.

또한 weight는 \(10^-6\)을 갖는 \(L_2\) regularization을 적용한다. (\(Cost = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \{L(y_i,\hat{y_i})+\frac{\lambda}{2}|w|^2\}\))

그런 다음 feature prediction network의 ground truth-aligned predictions에 수정된 WaveNet을 학습한다.

즉, prediction network는 teacher-forcing mode에서 실행되며, 각 예측 프레임은 인코딩된 입력 시퀀스와 ground truth spectrogram의 해당 이전 프레임에 따라 조절된다.

이렇게 하면 각 예측 프레임이 target waveform samples과 정확하게 정렬(align)됩니다.

\(B_1 = 0.9, B_2 =0.999, \epsilon = 10^-8\) 그리고 fixed learning rate는 \(10^-4\)인 Adam optimizer를 사용하여 synchronous update하는 32개의 GPU에 분산된 128개의 batch size로 학습한다.

It helps quality to average model weights over recent updates.

따라서 0.9999의 붕괴로 업데이트 단계에 걸쳐 network parameters의 exponentially-weighted moving average을 유지한다. 이 버전은 추론에 사용된다([29] 참조).

수렴 속도를 높이기 위해, mixture of logistics layer의 초기 출력을 최종 분포에 더 가깝게 연결하는 127.5의 인수만큼 waveform targets를 확장한다.

모든 모델은 단일 전문 여성의 24.6시간의 음성인 미국 영어 데이터 세트에서 학습한다.

datasets의 모든 text는 철자가 명시되어있다. 예를 들어 “16”이 “sixteen”으로 쓰여있다. 즉, 모델은 모두 정규화된 텍스에 대해 훈련한다.

3.2. Evaluation

inference mode에서 음성을 생성할때, ground truth targets을 알고 있지 않다.

따라서, 이전 단계의 예측 출력은 훈련에 사용되는 teacher-forcing configuration과 대조적으로 디코딩 중에 입력된다.

datasets의 test set에서 100개의 fixed examples를 evaluation set로 랜덤하게 선택했다.

이 set에서 생성된 오디오는 Amazon의 Mechanical Turk와 유사한 human rating service로 전송되며, 각 샘플은 0.5점씩 증가하여 1부터 5까지의 scale로 최소 8명의 평가자가 평가했으며 주관적인 mean opinion score (MOS)가 계산된다.

각 평가는 서로 독립적으로 수행되기 때문에 서로 다른 두 모델의 출력은 평가자가 점수를 할당할 때 직접 비교되지 않는다.

evaluation set의 instances는 training set에 절대 나타나지 않지만, 두 세트 사이에는 몇가지 반복 패턴과 공통 단어들이 있다.

우리가 비교하는 모든 시스템이 동일한 데이터에 대해 훈련되기 때문에, relative comparisons는 여전히 의미가 있다.

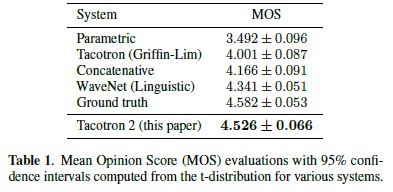

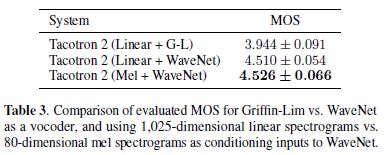

Table 1은 다양한 이전 시스템과 본 논문이 제시한 방법을 비교한 것이다.

mel spectrograms를 features로 사용하는 효과를 더 잘 분리하기 위해, 위에서 소개한 WaveNet architecture와 linguistic features[8]에 조건화된 유사하게 수정된 WaveNet과 비교한다.

또한 linear spectrograms을 예측하고 Griffin-Lim을 사용하여 오디오를 합성하는 original Tacotron과 비교하면, 두가지 모두 Google에서 생산에 사용되어온 concatenative [30]와 parametric [31] baseline systems을 사용한다.

우리는 제안된 시스템이 다른 모든 TTS 시스템보다 훨씬 성능이 뛰어나고, 결과적으로 MOS가 ground truth audio와 견줄 만한 성능을 보인다는 것을 발견했다.

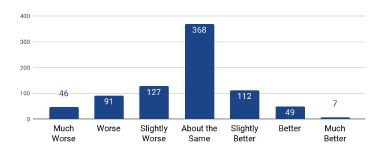

또한 시스템에 의해 합성된 오디오와 ground truth에서 side-by-side evaluation를 수행한다.

각 발언 쌍(pair)에 대해 평가자는 -3(실제보다 훨씬 합성 불량)부터 3(실제보다 합성 성능이 훨씬 우수)의 점수를 부여해야 한다.

\(-0.270 \pm 0.155\)의 전체 평균 점수는 우리의 결과보다 ground truth에 대한 작지만 통계적으로 의미있는 선호도를 평가자들이 가지고 있음을 보여준다.

자세한 설명은 Figure2를 참조

평가자들의 의견은 우리 시스템에 의해 가끔 잘못된 발음이 이런 선호도 값의 주된 이유이다.

우리는 Deep Voice 3[11] 의 부록 E에서 커스텀한 100문장 test set에 대해 별도의 등급 실험을 실시하여 4.354의 MOS를 얻었다.

우리 시스템의 error modes에 대한 수동 분석에서 각 범주의 오류를 독립적으로 계산하고, 0 문장은 반복 단어를 포함하며, 6 문장은 오발음을 포함하며, 1 문장은 건너뛰는 단어를 포함하며, 23 문장은 잘못된 음절이나 단어를 강조하거나 부자연스러운 음절을 포함하도록 주관적으로 결정되었다.

가장 많은 문자를 포함하는 입력 문장에서 single case에 End-point prediction이 실패했다.

이러한 결과는 우리 시스템이 전체 입력에 안정적으로 참여할 수 있지만 prosody modeling을 개선할 여지가 있음을 보여준다.

마지막으로, out-of-domain text에 시스템의 일반화 능력을 테스트하기 위해 37개의 뉴스 헤드라인에서 생성된 샘플을 평가한다.

이 작업에서, 모델은 \(4.148 \pm 0.124\)의 MOS를 받은 반면 언어적 features에 조절된 WaveNet은 \(4.137 \pm 0.128\)의 MOS를 받았다.

이러한 시스템의 출력을 비교하는 side-by-side evaluation은 \(0.142 \pm 0.338\)의 결과에 대한 통계적으로 의미있지 않은 선호도인 virtual tie를 보여준다.

평가자 코멘트를 조사하면 우리의 neural system이 보다 자연스럽고 인간적으로 느껴지는 음성을 생성하는 경향이 있지만, 예를 들어 이름을 처리할 때 발음에 어려움을 겪는 경우가 있었다.

이 결과는 end-to-end 접근 방식에 대한 문제를 지적한다. 즉, 사용 의도를 다루는 데이터에 대한 교육이 필요합니다.

3.3. Ablation Studies

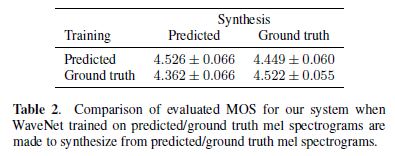

3.3.1. Predicted Features versus Ground Truth

모델의 두 가지 구성 요소는 별도로 학습되었지만, WaveNet 구성 요소는 학습을 위해 예측된 features에 따라 달라진다.

이러한 문제의 대안은 ground truth audio에서 추출한 mel spectrograms에서 WaveNet을 독립적으로 학습하는 것이다. Table 2를 참조

예상한 대로, 훈련에 사용된 특징이 추론에 사용된 것과 일치할 때 최고의 성능을 얻는다.

그러나, ground truth 특징에 대해 훈련하고 예측된 특징에서 합성하도록 만들 때, 결과는 그 반대보다 더 나빴다.

이는 예측 spectrograms이 oversmooth되고 ground truth보다 덜 상세해지는 경향에 기인하며, 이는 feature prediction network에 의해 최적화된 squared error loss의 결과이다.

ground truth spectrograms에 대해 학습할 때, 네트워크는 oversmooth된 features에서 high quality speech waveforms을 생성하는 방법을 학습하지 않는다.

3.3.2. Linear Spectrograms

- mel spectrograms을 예측하는 대신, linear-frequency spectrograms을 예측하는 훈련을 실험하여, Griffin-Lim을 사용하는 spectrogram invert가 가능하다.

DeepVoice2[10]에서 언급했듯이, WaveNet은 Griffin-Lim과 비교하여 훨씬 더 높은 품질의 오디오를 생산한다.

그러나 linear-scale 또는 mel-scale spectrograms의 사용 사이에는 큰 차이가 없다.

따라서 mel spectrograms의 사용은 좀 더 컴팩트한 표현이기 때문에 엄격하게 더 나은 선택인 것 같다.

향후 연구에서 the number of mel frequency bins 대 audio quality 사이의 trade-off을 탐구하는 것은 흥미로울 것이다.

3.3.3. Post-Processing Network

predicted future frames의 정보를 디코딩 하기전에는 사용할 수 없었기 때문에, feature predictions을 개선하기 위해 디코딩한 이후 past frames과 future frames을 통합하기 위해 convolutional postprocessing network를 사용한다.

그러나 WaveNet은 이미 convolutional layers를 포함하고 있기 때문에 WaveNet이 vocoder로 사용될 때 post-net이 여전히 필요한지 의문이 들 수 있다.

이 질문에 답하기 위해 post-net이 있고 없고를 비교한 결과, post-net이 없으면 \(4.429 \pm 0.071\)의 MOS 점수를 얻었고 post-net이 있으면 \(4.526 \pm 0.066\)의 MOS를 얻었다. 이는 경험 적으로 post-net이 여전히 네트워크 설계에 중요함을 의미한다.

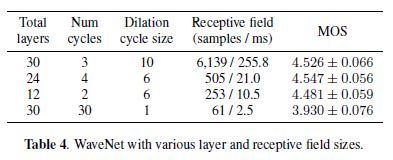

3.3.4. Simplifying WaveNet

WaveNet의 feature를 정의하는 것은 layers의 수에 따라 receptive field를 기하급수적으로 증가시키기 위한 dilated convolution의 사용이다.

mel-spectrograms이 linguistic features보다 waveform 표현이 훨씬 더 가깝고 mel-spectrograms이 프레임에 걸친 장기적인 종속성을 이미 포착하기 때문에

작은 receptive field를 가진 shallow network가 만족스럽게 문제를 해결했다는 hypothesis를 테스트하기 위해 receptive field 크기와 layers의 수가 바뀌는 models를 평가한다.

Table 4에 나온 것처럼, 우리는 우리의 모델이 baseline model의 30개 layers와 256 ms에 비해 10.5 ms의 receptive field를 가진 12개 layers를 사용하여 고품질 오디오를 생성할 수 있다는 것을 발견했다.

이러한 결과는 DeepVoice[9]의 large receptive field size가 오디오 품질에 필수적인 요소가 아니라는 것을 확인시켜 준다.

그러나, 우리는 복잡성의 감소를 가능하게 하는 것은 mel spectrograms 조건화 선택이라는 가설을 세웠다.

한편, dilated convolutions을 완전히 제거하면 receptive field는 baseline보다 두 자릿수가 더 작아지고 stack이 baseline model만큼 깊어도 품질은 크게 저하된다.

이는 고품질 사운드를 생성하기 위해 waveform samples의 time scale에 충분한 context가 모델에 필요하다는 것을 나타낸다.

4. CONCLUSION

본 논문은 sequence-to-sequence recurrent network를 attention와 결합하여 수정된 WaveNet vocoder를 사용하여 멜 스펙트럼 프로그램을 예측하는 fully neural TTS system인 Tacotron2에 대해 설명한다.

결과 시스템은 Tacotron-level prosody 와 WaveNet-level audio quality로 음성을 합성한다.

이 시스템은 복잡한 feature engineering에 의존하지 않고 데이터에서 직접 훈련할 수 있으며, 자연스러운 인간 음성에 가까운 최첨단 음질을 달성한다.

6. REFERENCES

[1] P. Taylor, Text-to-Speech Synthesis, Cambridge University

Press, New York, NY, USA, 1st edition, 2009.

[2] A. J. Hunt and A. W. Black, “Unit selection in a concatenative

speech synthesis system using a large speech database,” in Proc.

ICASSP, 1996, pp. 373–376.

[3] A. W. Black and P. Taylor, “Automatically clustering similar

units for unit selection in speech synthesis,” in Proc. Eurospeech,

September 1997, pp. 601–604.

[4] K. Tokuda, T. Yoshimura, T. Masuko, T. Kobayashi, and T. Kitamura,

“Speech parameter generation algorithms for HMMbased

speech synthesis,” in Proc. ICASSP, 2000, pp. 1315–1318.

[5] H. Zen, K. Tokuda, and A. W. Black, “Statistical parametric

speech synthesis,” Speech Communication, vol. 51, no. 11, pp. 1039–1064, 2009.

[6] H. Zen, A. Senior, and M. Schuster, “Statistical parametric

speech synthesis using deep neural networks,” in Proc. ICASSP,

2013, pp. 7962–7966.

[7] K. Tokuda, Y. Nankaku, T. Toda, H. Zen, J. Yamagishi, and

K. Oura, “Speech synthesis based on hidden Markov models,”

Proc. IEEE, vol. 101, no. 5, pp. 1234–1252, 2013.

[8] A. van den Oord, S. Dieleman, H. Zen, K. Simonyan, O. Vinyals,

A. Graves, N. Kalchbrenner, A.W. Senior, and K. Kavukcuoglu,

“WaveNet: A generative model for raw audio,” CoRR, vol.

abs/1609.03499, 2016.

[9] S. O¨ . Arik, M. Chrzanowski, A. Coates, G. Diamos, A. Gibiansky,

Y. Kang, X. Li, J. Miller, J. Raiman, S. Sengupta, and

M. Shoeybi, “Deep voice: Real-time neural text-to-speech,”

CoRR, vol. abs/1702.07825, 2017.

[10] S. O¨ . Arik, G. F. Diamos, A. Gibiansky, J. Miller, K. Peng,

W. Ping, J. Raiman, and Y. Zhou, “Deep voice 2: Multi-speaker

neural text-to-speech,” CoRR, vol. abs/1705.08947, 2017.

[11] W. Ping, K. Peng, A. Gibiansky, S. O¨ . Arik, A. Kannan,

S. Narang, J. Raiman, and J. Miller, “Deep voice 3: 2000-

speaker neural text-to-speech,” CoRR, vol. abs/1710.07654,

2017.

[12] Y. Wang, R. Skerry-Ryan, D. Stanton, Y. Wu, R. J. Weiss,

N. Jaitly, Z. Yang, Y. Xiao, Z. Chen, S. Bengio, Q. Le,

Y. Agiomyrgiannakis, R. Clark, and R. A. Saurous, “Tacotron:

Towards end-to-end speech synthesis,” in Proc. Interspeech,

Aug. 2017, pp. 4006–4010.

[13] I. Sutskever, O. Vinyals, and Q. V. Le, “Sequence to sequence

learning with neural networks.,” in Proc. NIPS, Z. Ghahramani,

M. Welling, C. Cortes, N. D. Lawrence, and K. Q. Weinberger,

Eds., 2014, pp. 3104–3112.

[14] D. W. Griffin and J. S. Lim, “Signal estimation from modified

short-time Fourier transform,” IEEE Transactions on Acoustics,

Speech and Signal Processing, pp. 236–243, 1984.

[15] A. Tamamori, T. Hayashi, K. Kobayashi, K. Takeda, and

T. Toda, “Speaker-dependent WaveNet vocoder,” in Proc.

Interspeech, 2017, pp. 1118–1122.

[16] J. Sotelo, S. Mehri, K. Kumar, J. F. Santos, K. Kastner,

A. Courville, and Y. Bengio, “Char2Wav: End-to-end speech

synthesis,” in Proc. ICLR, 2017.

[17] S. Davis and P. Mermelstein, “Comparison of parametric representations

for monosyllabic word recognition in continuously

spoken sentences,” IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech

and Signal Processing, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 357 – 366, 1980.

[18] S. Ioffe and C. Szegedy, “Batch normalization: Accelerating

deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift,” in

Proc. ICML, 2015, pp. 448–456.

[19] M. Schuster and K. K. Paliwal, “Bidirectional recurrent neural

networks,” IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, vol. 45,

no. 11, pp. 2673–2681, Nov. 1997.

[20] S. Hochreiter and J. Schmidhuber, “Long short-term memory,”

Neural Computation, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 1735–1780, Nov. 1997.

[21] J. K. Chorowski, D. Bahdanau, D. Serdyuk, K. Cho, and Y. Bengio,

“Attention-based models for speech recognition,” in Proc.

NIPS, 2015, pp. 577–585.

[22] D. Bahdanau, K. Cho, and Y. Bengio, “Neural machine translation

by jointly learning to align and translate,” in Proc. ICLR,

2015.

[23] C. M. Bishop, “Mixture density networks,” Tech. Rep., 1994.

[24] M. Schuster, On supervised learning from sequential data with

applications for speech recognition, Ph.D. thesis, Nara Institute

of Science and Technology, 1999.

[25] N. Srivastava, G. E. Hinton, A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and

R. Salakhutdinov, “Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural

networks from overfitting.,” Journal of Machine Learning

Research, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1929–1958, 2014.

[26] D. Krueger, T. Maharaj, J. Kram´ar, M. Pezeshki, N. Ballas, N. R.

Ke, A. Goyal, Y. Bengio, H. Larochelle, A. Courville, et al.,

“Zoneout: Regularizing RNNs by randomly preserving hidden

activations,” in Proc. ICLR, 2017.

[27] T. Salimans, A. Karpathy, X. Chen, and D. P. Kingma, “PixelCNN++:

Improving the PixelCNN with discretized logistic

mixture likelihood and other modifications,” in Proc. ICLR,

2017.

[28] A. van den Oord, Y. Li, I. Babuschkin, K. Simonyan, O. Vinyals,

K. Kavukcuoglu, G. van den Driessche, E. Lockhart, L. C. Cobo,

F. Stimberg, N. Casagrande, D. Grewe, S. Noury, S. Dieleman,

E. Elsen, N. Kalchbrenner, H. Zen, A. Graves, H. King, T. Walters,

D. Belov, and D. Hassabis, “Parallel WaveNet: Fast High-

Fidelity Speech Synthesis,” CoRR, vol. abs/1711.10433, Nov.

2017.

[29] D. P. Kingma and J. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic

optimization,” in Proc. ICLR, 2015.

[30] X. Gonzalvo, S. Tazari, C.-a. Chan, M. Becker, A. Gutkin, and

H. Silen, “Recent advances in Google real-time HMM-driven

unit selection synthesizer,” in Proc. Interspeech, 2016.

[31] H. Zen, Y. Agiomyrgiannakis, N. Egberts, F. Henderson, and

P. Szczepaniak, “Fast, compact, and high quality LSTM-RNN

based statistical parametric speech synthesizers for mobile devices,”

in Proc. Interspeech, 2016.